‘Goa se aaya mera dost, dost ko salaam karo.’ We have someone very special at your Adda today. He is among the very few Indian blogger’s who has been featured in Lonely Planet Travel Blog awards. His blog epitomes the saying ‘A picture speaks a thousand words.’ At the turn of the century he returned to Bombay from Goa, which according to him was not an easy decision to make. Today at your Adda, we have Anil Purohit who is the brains behind the very popular travelogue ‘Windy Skies‘ interviewed. This interview is special as every answer has a photo associated with it. 🙂 So are you ready to enter the world of Anil Purohit? Here we go.

Q: When and why did you start blogging?

There was no one single reason. I considered starting one in 2003, only doing so in early 2004 though the blog didn’t pick up momentum until 2006.

It was a combination of trying out the medium, being able to share a link to the blog and have friends to read it, and a way to record my time in Mumbai, as in a diary. It was an attempt to mark time, to account for the tangibles one seeks beyond the work desk, and I sought mine in travel and photography, stringing thoughts together to articulate a passing moment. Moreover, I wanted to put my accounts of travels online, possibly with the hope of connecting to kindred souls, and share my own take of travel and traveling. And the blog would be where I’d have the liberty to choose aspects of travel that interested me, notably the everyday, the mundane, the ‘regular’ folks one meets when traveling, and street corners among other things.

I didn’t post much when I started out, possibly due to a lack of critical mass of desi bloggers and blogging in those days to spur the need to add my own voice to the existing multitude, much less know where the multitude hung out, if it indeed did. I can’t remember seeing online addas back then. I suppose the lack of any visible validation of any sort was a factory to many bloggers starting out back then.

While one seeks validation of one’s thoughts, as in feedback and engagement, one equally seeks validation of the need to put in the effort as with starting and maintaining a blog, more so if there’s little or no clarity on where it fits in in the context of the genre and the audience, a fairly unknown quantity back then, compounded no doubt by a lack of understanding of the potential of the online space. Only now has the potential manifested itself. It’s one thing to fulfill a need within as with diarists of yore, but quite another to create an online need for it, never easy. Possibly one reason why the Indian blogosphere is full of abandoned blogs dating back from 2004-2006, and even later.

Q: Goa to Mumbai. When and why did it happen? How did you cope with the change and how was/is the experience of shifting?

I came to Mumbai from Goa in search of livelihood at the turn of the millennium. The shift happened in two phases. While the necessity of a job was a strong enough driver to force coping with the situation, the challenge was in coming to terms with Mumbai’s overall culture, for no two places anywhere could be as different as Mumbai and Goa.

Unlike traveling, where you’re a temporary resident of the place, a key reason why it’s easy to adapt when there are no degree of permanence to your footfall, is engaging with the visited place to experience and survive the transient moment in all its joyous glory. Shifting to Mumbai was different from traveling to the city for a visit, more so in its absolute contrast with Goa.

I missed Goa’s unhurried pace, sussegad as they say in the native language, Konkani. So, if you’re doing nothing particularly productive or not doing what everybody else thinks you should be doing, then few will doubt your sanity, like they might do in Mumbai assuming they’ve a moment to spend to reflect on it. A key difference.

Goa will lend you space to be yourself. Mumbai will lend you space that’s left over after everyone has had their share of it. I did miss Goa’s natural beauty, the bird-life, and quiet roads that meander through even quieter localities, with voices from the street floating in through the windows, mingled with the call of the village baker on his rounds through the neighbourhood, followed by fisherwomen calling attention to their presence as they haul baskets of fish from door to door, each slowing the pace of life down to a point of deep comprehension of the evolving moment and its assimilation into each waking moment, into the subconscious.

It is still possible to find folks in Goa who have the time to spare to debate, discuss, and generally talk about everything and nothing in particular at the same time. Outside of Goa’s city centers, stopping by family run inns or gaddos as they are called in Konkani, for delicious pav bhaji, the taste of locally made bun-shaped bread with steaming gravy accompaniment before continuing to the ferry point where you wait with the others for the river ferry, while watching kingfishers scream overhead is one such moment from the many that makes Goa delightful to explore and live in.

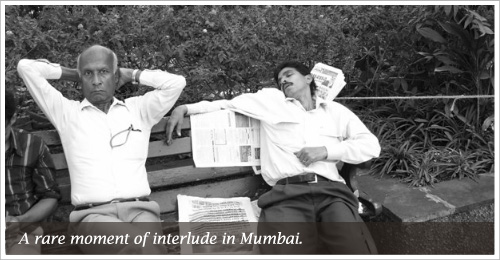

In contrast Mumbai is like a Twitter timeline, people, moments, experiences, possibilities, events, festivals, voices, all scrolling down in a mad rush each time you refresh your day on the hour, on the minute. While the rush of Mumbai timeline ensures you miss nothing that you cannot compensate for the second time around given the city’s abundance of it all, it also ensures you miss everything for the lack of space time has, in assimilating the experiences without being tantalized the very moment by the next one the city offers in the very next moment, or hour if not the day. The problem of plenty is also the problem empty.

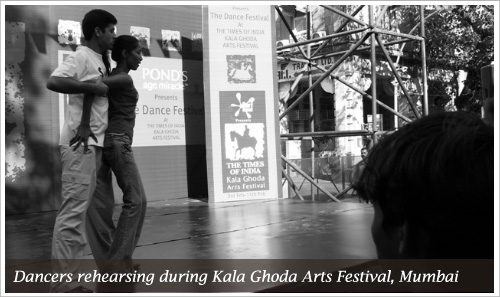

While Mumbai is everything that Goa is not, the scope of the diversity of experiences on Mumbai’s streets, the vibrancy of its cultural corners, the possibilities of its interactive spaces, the abundance of the events it plays host to week on week through the year on year, the resilience of its people and their stories, all served to make my transition from Goa to Mumbai easier, once I re-oriented my expectations to match the possibilities that Mumbai opened up.

I revel in Mumbai’s ability to engage the senses several times all at once even at the cost of it being too much in too little time. The streets are where its humanity finds expression in the most unique ways, it is where every possible human need for ingenuity is accounted for, sometimes in improvisations that taps into India’s felicity for jugaad. And that must surely count among the city’s most endearing traits. Mumbai is the devil, and the deep sea, both at the same time. And I’ve relished the time since the time I dropped my anchor in the maelstrom here. It’ll take a strong wind to push my boat out to sea, once more.

But the shifting, the changing of homes each time I had to move about the city, the compulsion of surviving crowds in making the daily commute to work and back, of not being able to get into public transport without running sweat in the process, of not being able to walk without watching out for others to avoid bumping into, the potholed roads, of having to battle for space most moments, and the rarity of serendipitous moments are among the things in Mumbai I wish I could do without on a daily basis.

Having said that I cannot believe, and I may well be wrong on some counts, there’s a city on earth that can rival Bombay for what it was, for what it is, and for what it can still be.

Change is the only constant. And each constant is a variable.

Q: After so many years in Mumbai, do you think you’re more of a Mumbaikar now?

It depends upon how one looks at it. Adapting to Mumbai is no different from riding a wave as opposed to fighting it. Fight it, and you get overwhelmed. I’ve learned to take the good with the bad and emerged from it none the worse for the wear. At times it’s like living on the edge, at other times, the edge sharpens one in some ways. So I suppose it qualifies me to be a Mumbaikar, for now that is. Mumbai is a remarkable city of the street, and bylanes.

In quite another way I think I’ll continue to be an ‘outsider’. Not quite an ‘outsider’ in the manner of Meursault in the Albert Camus book of the same name, but from not having lived through its transformation to an overcrowded megalopolis of today, whose mostly mixed community neighbourhoods largely lack distinct community character in the Bombay of before as say in what one still gets to experience in the Dadar Parsi Colony, and a few surviving ones. I did not live through this change. Many others, Mumbaikars, did. And it tells.

The transformation from a once vibrant, spacious, cultural and community specific neighbourhood, distinguished by the community ethos and the identity of early settlers and their descendants, has largely stripped the present day Mumbai street of a certain atmosphere. Included is the steady loss of its architectural heritage to reconstruction or to modification of the architectural character of the neighbourhood, as new owners, often from outside the original community, effect changes not in keeping with the original architectural character. As Willy Felizardo once pointed out to me a garishly done home of a family that had moved into an old house in the quaint neighbourhood of Khotachiwadi, among the older Mumbai settlements. Willy’s artistic bent of mind was not too happy to be losing the neighbourhood landscape he grew up with.

To survive the travails of everyday as a recent migrant, is different from surviving those brought on by such a transformation, for in the latter there’s an acute sense of loss, brought on by a realization that the change is irreversible. Living through a loss of original identity as shaped by one’s city, while seeking to adapt to the new one being shaped by factors over which one has little or no control, is central to the depth of feeling for a place of residence; an inheritance of loss in a way. Either one lives through it over a life span, or one inherits it from ancestors. And it’s key, in many ways, to being a Mumbaikar.

In this aspect it’d take me a fairly long time to become a Mumbaikar.

Q: Windy Skies is a very interesting blog name. Why did you choose that name and how does it relate to the content you write on your blog? What is the story behind it?

The sky is a constant on my travels, has always been. And as with any constant, there’s a certain timelessness associated with the sky. Those early memories of traveling through India’s hinterland, mostly South India, has much to do with why I named my blog Windy Skies.

Through windows of buses that I traveled in during summer vacations from school, I was mesmerized by the sight of sunflower fields and the blue skies overhead, more so when winds would herd clouds along towards the horizon. I would look for shapes in clouds floating in the skies and watch them seemingly interact among themselves as they moved along, their shadows often trailing behind in fields growing Cotton, Sunflower, Jawar, and the like. At night constellations and stars in the skies kept me company to the fierce rattling of the bus over remote roads, traveling in a dark bubble except for the headlights.

In vacations from school, since the time I was seven years old, I would travel across a wide swathe of the Deccan Plateau with my parents, mostly my mother since my father would be busy at his office in Goa, visiting relatives along the way, staying with them, before visiting more uncles and aunts, almost always traveling by bus, the dreaded K.S.R.T.C. red buses. Later, as I grew older, I would set off on my own through the same arc sweeping across 500 kms. and back the same route, stopping along the way to renew blood ties and reconnect with the land of my forefathers, and where we came from.

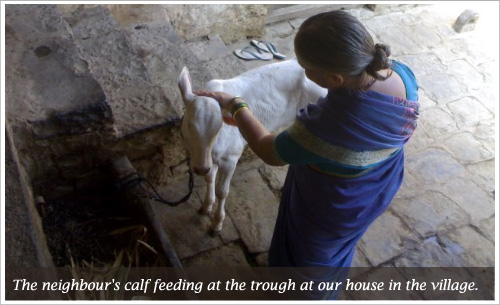

At my ancestral home in a village located in Sindgi Taluka, my uncle made a living off agriculture from farm land that lay a few kilometers out from the village centre, in the direction of Afzalpur, and also from a flour mill my paternal grand-father had started. In the courtyard three buffaloes and two oxen fed at the trough, and I would help with feeding them. The calves would be tied near the Tulsi Vrindavan by the store room that held farming implements, at other times, tenants, and at yet other times accommodating relatives during religious functions.

I was probably too young to herd our three buffaloes, so when the farm hand took our buffaloes out for feeding, I would occasionally ride them out to their grazing fields, sitting atop a buffalo, resting my hands at either ends of the stick crossed behind my neck, mimicking other herdsmen doing likewise. And there would be many of these lumbering creatures around, those belonging to our neighbours as well. The moment the herd left the village, blue skies opened up the landscape. Feeling the wind on my face atop the buffalo I would be precariously balancing on while the farmhands goaded them along, the bustle of the village we had left behind still echoing in my ears, is among my memorable memories.

Landscapes of my childhood in India’s hinterland

While out among the open fields, running through Sunflower fields in the farmland adjoining ours, playing hide and seek with amused farmhands, while occasionally laying down among the sunflowers in the quiet of India’s hinterland, with only the sky, and the clouds riding the winds for company, are moments from my childhood and growing up years I remember often.

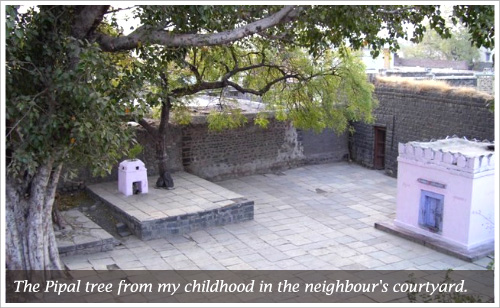

And at night, when the family retired to the terrace to beat the heat, in the gaze of an old Pipal tree where an eagle family had its home from as far back as I can remember, amid chimneys smoking from kitchen fires, I had the night sky to myself, and to pass time, my older cousin and I would look for patterns among the stars, sometimes carving the sky up between us and counting the stars in our halves. His half would invariably have more stars than mine, until I learned to count quicker. Then I grew up!

Many an evening in the village on vacation from school was spent flying kites from the terrace, competing with village kids my age flying their own kites from their roof tops, each goading the their kite into touching the skies. I got to be competent at flying kites, but not so much at kite fighting, losing my kite every once in a while to the depredations of fighter kites. And on our after-school bicycling trails through the hills back home in Goa, the lot of us meandered about the back roads where scarcely a soul was to be found, we had the skies for company as we rode the wind at speed, often racing each other across the countryside.

When I think about it now, I suppose the best journeys are those that offer possibilities beyond what one has managed to see or experience, much like the horizon that keeps shifting as you travel towards it, goaded on by white clouds in the sky, driven along by wind. Hence the name, Windy Skies.

Q: You are also a nature lover. If you were to be a part of nature, then what would you choose to be and why?

Growing up in Goa, and having trekked in wildlife sanctuaries across several Indian states during school and college, it was only natural for nature to wriggle into my own landscapes. I think I’d swap places with a bird.

As to why? Well, maybe to be ‘above it all’, or maybe I’d love to be an ‘eye in the sky’ to watch over all you mortals, or even better I wouldn’t have to buy tickets for my travels or worse still I wouldn’t have to agonise over whether I would get the tickets considering how corrupted by agents the IRCTC seems to be these days. Okay, I was kidding.

I’d imagine it has to do with their agility, a sense of freedom, wide open spaces to let their fancy play out, for a bird’s eye view of the world, for being able to see what lay behind the corner in the road even before getting to it, for being able to ride the winds for long, long distances, for the colours nature blesses them with as if it revels in playing out its painting instincts on their wings, and many more.

Like with life, possibilities in the skies are endless. The bird it has to be, for in no other form can the earth ever be your own, private playground to play with.

Q: You suggest that publishers should start marketing their books by giving it in the hands of the commuters in Mumbai local trains. You also started India Book Project to capture in pictures what people are reading during traveling. What triggered this brilliant idea? Why did you discontinue it? We would love to see that series again on your blog.

I started the India Book Project to create online space for books and the reading habit by documenting instances of people reading books with the objective of expanding it later to document reading spaces in general and their impact on the dynamics of reading.

While there’s enough space online already for books and book reviews, there’s none or very little space online pertaining to reading spaces and the dynamics of reading in everyday spaces like for instance reading books in trains and buses, at bus stops, railway stations; essentially seeking to relate to people reading books in public spaces they share with others, a geographic touch-point I believe that others can readily relate to.

It started as I noticed commuters reading books in local trains on my way to work and back. Buried in the books they were reading, they had created a very private space for themselves where there was none, the reading cocoon withstanding the crowds buffeting them along the way to office or home.

My project photographing book readers on the local trains is in effect a social documentary, articulating visually to the wider public what most of us traveling by local trains see. Among the key purposes is to have people viewing the pictures to relate to the discomfort readers go through in trying to read in rush hour locals, and hopefully make them aware of the need for space in pursuing what is in effect a cultural necessity. Every culture lives between the pages of a book. A book stills time in more ways than one. It provides us with context of time and place.

The project also attempts to freeze these reading moments for the viewing eye to linger over them and hopefully have them reflect on the face, the concentration, the book title, and the very effort of reading. In some ways I hope this will sensitise the viewers to what is an important cultural trait. It is what all social documentaries seek to achieve – a sensitization of the situation and/or circumstance.

I haven’t discontinued the series, only paused it for the moment. And now that I’ve collected more material for subsequent installments, it should be possible to see the next parts of the series showing the books that commuters read on Mumbai locals on my blog sooner than later.

A book read on a crowded local in Mumbai does much to raise its visibility. Unlike book reviews or advertisements, a fellow traveler reading a book is its strongest advocate. If the same traveler brings the book back the next day, his continuing with it serves as an even stronger reminder to his fellow travelers, many of whom will likely be the same set of people as in sharing similar attributes or a set of similar attributes.

To publishers seeking to market their books I would suggest they put their titles in the hands of a few of their marketers and get them onto local trains at different times of the day, not merely hold the book in their hands but actively read it. Alternate and repeat the exercise over a month and see the visibility for the book rise. A book cover that hides a reading face is a book cover that will be remembered, more so when it has a captive audience that’s bored looking out the window of a train they’ve been riding for a decade.

I would suggest they bring the reading-commuters into their fold. Like they would send books to book reviewers to write reviews, they should look at doing the same to commuters who read books on the train on their daily commute.

Q: Your qualification is in Computer Science. Does your day job revolve around this field? We all lead a routine day to day life when we are not pursuing our interests. Apart from traveling and discovering people and places, how does your normal day seem like? How did your interest in traveling start?

I started out as a trainee programmer in the Applied Technology group of an IT company, learning the ropes, keeping my eyes open. It was a R&D division and since I was among the youngest in the team I was treated kindly, had my queries answered, and generally had a good time, and got to share space with one Mr. Chitnis who would publish all kinds of research papers and get invited by Microsoft, if I remember correctly, to present them at their conclaves / conferences. In the team, I was probably among the only few not to have graduated from the IIT, and by consequence a lesser mortal.

While I’ve remained on the technology side of things, I’ve moved on to the design aspect of applications.

On a normal day, it’s the same routine as with any normal person – work, potter around the house, spend time with family, read a bit, watch the news a bit, surf the net a bit, write once in a while, and plan for the weekend for sights around the city or laze at home.

As for traveling, I suppose it runs in the family. My parents have traveled and covered more miles than I can ever hope to emulate, even if much of it was by way of attending family functions and the like, while my father’s job involved extensive traveling even if it was restricted to Goa.

I would credit my father with giving me the traveling bug. As a child he would take me along when he traveled on work to most parts of Goa over time. Like for instance when CHOGM (Commonwealth Heads Of Government Meeting) came calling to Goa in the early eighties, about the time when I had finished with primary schooling, the Goa Govt. was tasked with ensuring that power lines in the region where the Commonwealth Heads of State were to gather were free of faults. This meant each connectivity along the route needed to be checked, through every village along the way, and as also the power lines along the entire stretch from Maharashtra to Goa, bringing in power to Goa. I tagged along with Dad to Kolhapur for sourcing the equipment for the same, and back from school I would then tag along with his team, crisscrossed Goa for stability checks. Goa does not produce its own power.

Vacations from school meant I would occasionally get to travel along with him for inter-state work, mostly to Maharashtra and Karnataka, Goa’s neighbouring states. I went along to Gadhinglaj where the 220 KV / 110 KV station providing power supply to Goa lay, not far from Gokak Falls. More work tours meant I got to travel with him to the Sharavathi Power Generating Station in Karnataka, and as also the power generating station at Jog Falls where it plunges down 830+ feet in a wash of ferocious white.

The Sharavathi river in Shimoga district has much of its river basin in the Western Ghats and is an intimidating sight, more so as the river thunders down from great heights as in Jog Falls. I had no camera then, was possibly not old enough to be trusted with one. I particularly remember enjoying the steep trolley rides that conveyed the staff to the generating station at the base of the falls.

Then there was the tour of the Supa dam as it was being built over the river Kali in Karnataka, eventually taking thirteen years to complete. I had never seen anything on that scale before, nor anything since then. At the time I was there, French engineers were about helping with the drilling. Machinery of the size I had not imagined before lay everywhere as overhead trolleys emptied construction material below. From the heights above the river, workers looked like ants, and down below all that I could see was vast areas of construction material.

Then there was Tilari. In one instance, all of Goa lost electricity when the main distribution line bringing power to Goa from Maharashtra snapped. Teams set out from Goa and Maharashtra from opposite ends to trace the cut in the line through its entire route. I was back from school and convinced my way in as to why my tagging along was important. All I did was watch from the window and get off the vehicle when the staff did, passing through terrain I would not have normally. It was memorable, more so when we eventually ended up at the Tilari Power Generation Plant in Maharashtra. The next day, Goan papers were full of problems the disruption in power supply had caused, and I was thankful for it for the journey I went on.

Then there were others, not to mention those around Goa, in the hills, in the villages, in the towns, across the river, like the instance when Dad was tasked with stringing the 110 KV power line across the Mandovi river at Banastari, eventually connecting Tivim. Small boats were used to carry the power lines, before requisitioning an Iron Ore barge to support the lines in the middle of the river before carrying it across. I tagged along there as well. It helped my classes finish by lunch time, and home-work could wait.

The travels to these and other places during my schooling years were equally interesting since they entailed roads off the beaten track. The people I met on these and other similar trips were ordinary folks like me, and were a diverse bunch if there ever was one, language, ethnicity, and culture.

Later, during vacations from college, I moved on to traveling on trekking and wildlife camps organized by WWF – India, primarily to Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and within Goa. On my own I made for Karnataka, and to Madhya Pradesh with a friend. The Kanha Wildlife Sanctuary was a treat. The journeys to each of these places were equally interesting for the routes I had to take to reach them.

For instance, to get to the Annamalai Wildlife Sanctuary from Goa, I got on a bus for the overnight journey to Mangalore, made a detour to Udupi and back, then boarded the train for Coimbatore, before getting onto to a bus for Pollachi, and eventually whiling away time waiting for the bus, one of the only four to operate in the day, to take me to Topslip in the Annamalai Wildlife Sanctuary. And many things happened along the way, enough to warrant a page of their own, not in the least when I overshot Coimbatore and reached Tirupur. It meant I had to take a bus back to Coimbatore. In attempting to return to Coimbatore, no one I met in Tirupur early that morning understood any language other than Tamil, and I understood no Tamil. And those were the days when you couldn’t even book train tickets online! And I was travelling alone. It meant I had to take my luggage into the small loo where I could barely fit in, let alone my suitcase and rucksack.

Ah, the joys and pains of being bitten by the travelling bug. Priceless.

Q: Do you ever get stuck when writing an entry? What do you do then?

I do. Much of my writing I squeeze for after work hours. In the pre-Internet days, when few had access to the Internet outside of city centres, it was easier to pick up the broken thread and finish writing the piece, for there was nothing else to distract you at your writing desk, before and after the break in the flow.

Now, we do not have that luxury, so when I get stuck in the middle of an entry, I surf like I suppose many will when they get stuck similarly, and then get caught up in surfing the Internet instead of picking up the broken thread.

It helps to let it be by itself for sometime, to put some distance between self and the writing. And if there’s sufficient pressing needed to complete it, like I sometimes do with deadlines to meet for magazine and newspaper submissions, I will eventually get back to it after I drag myself screaming and kicking to the desk, and then to the page. If it’s a blog post then the fact I haven’t posted one for long is sufficient motivation to pick up the broken thread, in as much as reliving the traveling all over again when writing it down is.

Most times it’s the gap in the details I’m structuring in the narrative that brings the post to a grinding halt. I’d assume it helps to get away for a bit, and return refreshed.

Luckily, I’m rarely stuck for ideas since most traveling will invariably involve a 101 things about it that one could write about, then there are pictures to help one out of tight situations. Bless the camera.

Q: Given an opportunity, would you like to account and publish all the travelogues, on your blog, in a book?

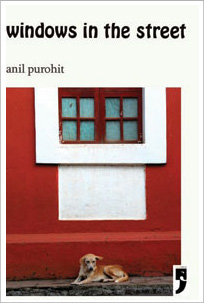

I surely would, and I’m fortunate to have a travel book scheduled to be published soon, possibly early next year. Yoda Press, founded by Arpita Das and based out of New Delhi, will be publishing my travel book titled Windows In The Street shortly.

The book is an account of my travels, impressions, and plain old meandering street side in India. While there’s much that India has to offer, much also depends upon what you go seeking on your journeys or are prepared to be surprised or engaged by. Sometimes it’s the mundane that refreshes on long journeys, other times it’s the quiet moment.

While some of the travel stories appearing in Windows In The Street are expanded from those posted on the blog, the others are new. I’m looking forward to seeing the book on the stands.

This travelogue is not over as yet. 🙂 Come back next week as we continue this journey alongwith Anil where he talks about his travel journeys, his favorite destinations and more.

I so loved this interview. And i can’t congratulate Blogadda enough for doing this. Totally wonderful, and so amazing to learn how he has developed his eye for stuff, given the huge amount of travelling he has done since childhood. And there is such a flow to his writing. As if what he writes about speaks into his ear .

I have always enjoyed reading Anil P’s wonderful and amazing blog, and I dont think the blogaddas should wait for a week to bring out the next part.

Very interesting interview. I enjoy Anil P’s blog and his style of writing. He has many stories to share, and he does so in a very captivating way.

I’m a big but fairly recent fan of windy skies, so it’s really great to get this insight into the author. Thanks to both of ye for a great interview

@ Suranga – Thank you for the kind words. A pleasure to know you’ve enjoyed reading the blog over time, and the interview. And thanks to BlogAdda for the set of questions. I probably travelled more as a kid and later, when I was schooling than I do now. We never had a camera back then, nor blogs or photo sharing platforms.

@ Daisy – Thank you. Wonderful knowing you like reading the many stories posted on the blog. Thanks.

@ Niamh – Thank you for your kind comment. It’s indeed a pleasure sharing some insights, and very encouraging to know you liked reading the interview.

@ Sudha @Smita – Thanks, for the sentiment expressed. Always encouraging to be told so.

Anil, I’m glad that I had a chance to experience part of your journey. Now it is more through surfing your blogs. It is always good to see things with your perspective.

Anil’s blog is a delight to read. He weaves a story around the pictures he takes.

I have been a reader of Windy skies for a while now & its a complete pleasure to be hearing so much of Anil speak about himself, where he comes from and his take on Mumbai, travel and why he does what he does on his phenomenal blog. I so respect his work. Thank you so much for interviewing Anil. P

Anil’s work is commendable. His style of telling stories for a photo of an ordinary looking daily life is just amazing.

His blog is a delight to read.

I loved this interview. And I congratulate Blogadda for giving us opportunity to read this.

It was really nice to read this interview. Have always enjoyed reading the posts on Windy Skies. Anil, Congrats on the forthcoming book! The title and the cover look great!

Have enjoyed the windy skies posts and looking forward to the forthcoming book and the sequel to this interview.